Kimberly-Clark Corporation, the maker of Kleenex, Huggies diapers, and toilet paper, was known for not measuring performance. Tenure in the company is what mattered and the company prided itself on a no-layoff policy. Employees had a job for life, and the company tolerated low performers.

This changed during the last recession when the product pipeline dried up, the cost structure was bloated, and the company’s growth stalled. The company realized that it needed to actually measure performance differently. Gone were the symbolic once-a-year PEs, replaced instead with a high-performance culture focused on increasing both revenues and profits. It could no longer do annual PEs with the widely used 9-box grid strategy (where the vertical axis measures potential and the horizontal axis measures performance), placing the lowest performers in the bottom left cell and the stars in the upper right cell. Instead, it added new software to track each individual’s actual work results more often and more closely. To drive productivity, they measured employees monthly and sometimes weekly. Low performers could no longer hide out for a year. They either improved or were terminated. Kimberly-Clark credits the new system for doubling its share price between 2008 and 2016.

Netflix relied on this same approach as it grew from a mail-order movie delivery business to an internet streaming and movie production juggernaut. Critical path performance—not skills, tenure, or diligence—mattered.

Patty McCord, Netflix’s former Chief Talent Officer, described a conversation with one employee who did product testing, a process that eventually became automated. The employee was incredibly upset, knowing she was about to lose her job. McCord tried to console her: "You're the best. You're incredibly good at what you do. We just don't need you to do it anymore."

Netflix made it clear in the culture section of their company website that it keeps "only our highly effective people." The site read: "Succeeding on a dream team is about being effective, not about working hard. Sustained 'B' performance, despite an 'A' for effort, gets a respectful generous severance package."

As McCord noted, this isn't an easy way to manage people. In fact, it might seem callous or downright unfair. But, Netflix believes that it is not responsible for each employee’s career. That is the employee’s responsibility. The company’s job (and yours) is to take care of their customers and their clients. As McCord argues, the company is building a business, not raising a family.

One way that companies like Netflix and Kimberly-Clark navigate the PE mess is to distinguish between inputs, throughputs, outputs, and outcomes. I suggest that you begin by doing the same. Then, you can decide which makes sense to include in your PE process.

“Inputs” are what you bring to the job—education level, professional licenses, work experience, skills, competencies, personal traits, values, etc. Many jobs require certain inputs in order for you to be hired. Your inputs get compared to those of the other applicants, and the person with the best set of inputs, in theory, should end up being hired. Companies often use proxies to measure input. For example, if you studied computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, the very best computer science school in the world (though Stanford and MIT might disagree), then you are assumed to be smart and know how to do high-level computer science. Likewise, if you worked at Google or Goldman Sachs, where there are thousands of applicants for each job, you are considered to be one of the best in your field.

“Throughputs” are what you actually do on the job—job responsibilities, job tasks, job activities, etc. These are the behaviors you engage in to accomplish certain tasks or to achieve certain goals. The throughput for an editor is to read and revise copy given to her by the writers. Another might be to decide which stories the writers will pursue. An R&D scientist’s throughput may focus on conducting experiments to determine which chemicals go into a prospective new drug. For an educator, throughput might be teaching classes. For a non-profit food bank employee, did they take the necessary steps to gather up and distribute food to needy people? Throughputs indicate that you are doing the expected job and, in most cases, that you are doing it in the expected manner.

“Outputs” measure the results from your work. Did the employees’ throughputs produce what was expected? After the editor revised the article, was the edited version better and more suitable for publication? Did the R&D scientist produce a marketable new drug? How many classes or students did the educator teach? How many people got food from the food bank or how many pounds of food were distributed? Outputs indicate that your throughputs led to something tangible.

“Outcomes” tell us if the outputs led to demonstrated value-added contributions to the bottom line of the organization. Outcomes tell us if our activities make a noticeable difference.

Did readers like and talk about the articles enough that they not only subscribed but their word-of-mouth recommendation led their friends to subscribe? Did the article generate so much reader interest that more advertisers wanted to place ads in the publication or pay a higher rate?

Did the scientist’s new drug not only work as expected, but also become a best-selling drug in its class, simultaneously helping improve more patients’ health outcomes while also generating both higher revenues and profits?

Did the educator’s students actually learn the material as demonstrated in a measurable way?

Did the people who got food from the food bank actually use it, and did their nutrition, health, food insecurities, and overall well-being improve?

Outcomes indicate whether our inputs, throughputs, and outputs move us along the critical path better, faster, smarter, more effectively, and/or more profitably. At its most basic, outcomes bring more money, either today or tomorrow, to the company and its investors. In terms of the critical path, outcomes and outputs are what we should be focusing on.

Too many PE processes overly focus on inputs and throughputs, while overlooking outputs and outcomes. The worst do not even include outcomes in the process. So, it should not be surprising that employees also overly focus on inputs and throughputs.

Try asking employees to indicate why the firm should keep them during a layoff or why they should get a raise. Invariably, virtually all trot out their inputs and throughputs. They will say that they have an advanced degree, a professional license, many years of experience, or work extraordinarily long hours — all inputs. Or, they will focus on the work they do, such as market research or vehicle maintenance. Very seldom do we hear what effects those inputs and throughputs produced. Even when employees learn the differences, they still cling to their inputs and throughputs to justify why they should be kept over someone else.

Hence, it should not surprise us when employees do not have outcomes to show for their work. People will say that “I did what they hired me to do,” as if that’s enough. Or, they’ll say that they worked really hard every day, pulled all-nighters, or cancelled their vacation. Sorry folks, that doesn’t cut it in today’s world.

This thinking is also reinforced by company PE practices. Consider Google, often considered an HR pioneer and trendsetter. John Doerr, the well-known Silicon Valley venture capitalist, convinced Google to adopt a PE process that he borrowed from Intel, known as OKRs, meaning Objectives and Key Results. The goal was similar to the management by Objectives movement of the 1960s and 1970s, i.e., have employees commit to goals and then measure whether they achieved them or not.

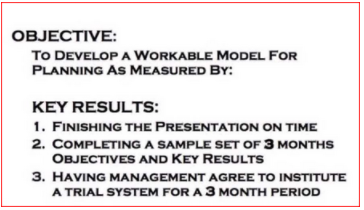

These OKRs ask employees what they plan to do over a time period. Here are two examples from Doerr’s presentation to Google, one for an employee in the planning department and another connected to the Google Blogger product.

You will notice that both OKRs primarily focus on throughputs, i.e., “finishing the presentation on time,” “completing a sample set of 3 months objectives and key results,” “Coordinate Bloggers 10th birthday PR efforts,” “and fix DCMA process, eliminate blog takedowns.” These are things the employee intends to do, not outcomes to achieve.

They do mention a few outputs, such as “Having management agree to institute a trial system for a 3 month period” and “Improve Blogger’s Reputation.”

In the 2nd set of OKRs, you can see how the employee’s throughputs and outcomes were measured on a 1.0 scale. It looks like he or she did speak at 3 industry events, which garnered the top score of 1.0, while not doing so well on the DCMA process, resulting in a score of .4.

But nowhere are outcomes mentioned. Why undertake all these actions if:

1) we don’t know how or if they are connected to the critical path; or

2) how you will measure the effects of these actions on the critical path.

Did speaking at 3 industry events lead to more customers, revenues, or profits? Or were these simply paid vacations enjoyed while also polishing a personal resume? Was the DCMA process more important to the critical path than the 3 industry speeches? If so, why were they not weighted to reflect their importance? Think about it: if the DMCA process was more important to Google’s critical path than those industry talks, earning a .4 score might have 5 to 10 times more (negative) effect on the critical path than the 3 industry talks, no matter how well the employee did.

Too many companies and, not surprisingly, their employees fall prey to believing that what you do necessarily leads to relevant outcomes and, thus, increased investor value. In fact, the investors need to be convinced that your work actually benefits the customers (and, in turn, them). Because of your work, are they (or other investors) willing to pay more, whether in the form of stock for public companies, donations for non-profits, or taxes for governments? On the flip side, can you show that losing you will have a negative impact on the profitability of the firm and a loss of their investment? Your outcomes demonstrate that what you do creates real economic and social value for them.

So far, we have been discussing positive outcomes. But employees can also produce negative outcomes. The can do shoddy work, which creates poor quality products and scrap that cannot be used. They can create accidents that harm people, stop production, and raise worker compensation rates. They can slow down a team, causing it to produce fewer or inferior products. They can constantly require assistance from top performers, thus lowering those stars’ productivity. They can also need more supervisory help than the other workers, which can require more low-level managers and their salaries.

A special case of poor performers are those workers who can be extremely productive but have such a negative impact on their co-workers that overall production and morale are lowered. We have all seen extremely productive people achieve some outstanding results but leave organizational destruction in their wake. Others then have to trail behind them to clean up the mess they made. When you sum the positive with the negative, it often nets out to zero or worse.

In my consulting work, I encountered a professional school’s associate dean who did a great job at many of the behind-the-scenes activities to make a school run effectively. He scheduled the classes, managed enrollments, took care of building logistics, orchestrated faculty teaching schedules and salary reviews, and led the accreditation review process. Both the Dean and University provost loved him, saying “he made the trains run on time.” Of course, that expression was also famously applied to the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, who led that country into the arms of Adolf Hitler and the disaster of World War II.

The comparison was apt and not lost on many faculty and students. The associate dean strong-armed the faculty, especially the younger ones, to do things his way. He forced them to accept teaching schedules and committee assignments that they believed interfered with their producing value-adding outcomes, threatening them with reprisals if they didn’t conform. Many groused among themselves and complained to senior faculty who had to make excuses for the associate dean’s behavior. He treated the administrative staff in a similar manner, brow-beating them into submission. The staff feared him and his temper. Not surprisingly, some of the best faculty and staff left for better work environments.

As for the students, he tolerated neither criticism nor suggestions for changes. In one fateful meeting with the students, he told them that the school lost money on them and that they should be happy to be able to go there. The enraged students, paying over $50,000 per year in tuition, complained to faculty and other administrators who were put in the awkward position of calming them down. Over five years, the faculty and student complaints soon grew loud enough that the university President forced not only the associate dean but the school’s dean, who had permitted this behavior, to step aside. A sigh of relief swept over the entire school.

The associate dean and the dean lost track of their critical path while they were “getting the trains to run on time.” High performing faculty and staff lead to very well trained, highly satisfied students who become alums that donate, hire future students, and generate positive words-of-mouth to attract more future students. High performing faculty, staff, and graduates create the brand that draws employers to hire, non-alum donors to give, agencies to give research dollars, and other top talent to want to work at the school. These deans failed to understand that throughputs can destroy positive outputs and outcomes.

A special, but terrible, case of destructive productivity is the star performer promoted to management who then becomes a bad boss. Some star individual contributors are not meant to be managers, whether by personal preference, personality, or the inability to shift gears to their new role as a manager. Yet very few can resist the temptation when upper management dangles the management-track promotion carrot in front of them. They bite— to their own detriment and that of the folks they will manage.

Bill was one such star performer. As the lead software programmer in a cyber-security firm, he had an intuitive knack for understanding how cyber thieves might try to attack large corporate computer systems. He also had a reputation for reducing 1,000 lines of code to 100 lines while increasing functionality and effectiveness.

Not surprisingly, his bosses thought he’d be a good fit for the management ranks, where he’d be able to leverage his skills across the team he’d supervise. Turned out, however, that Bill was not good at working through other people. He believed that everyone should be able to do what he did as an individual contributor. If not, they were either stupid or lazy. Instead of managing, he started looking over the shoulders of his subordinates, checking and correcting their work. He vented his frustrations on the team and told them that they had to work longer if needed to meet their targets. The more difficult projects he did himself. In other words, he became both a micro-manager and an individual contributor again.

Bill hated his new job and took it out on his team. In return, many of his team came to hate him. Most were looking to transfer to another department or outright quit for another firm.

Bill never understood that managing was different from being an individual contributor. He never adapted to his new role, learning the competencies necessary for success. In the process, he cost the company in two ways. On the one hand, the company lost much of the value that he provided to the critical path as an individual contributor. On the other hand, he destroyed the productivity of his subordinates. Instead of a win-win, he produced a lose-lose.

Critical Path Action Items

How do you define your job’s inputs, throughputs, outputs, and outcomes?

How do you measure your outputs and outcomes?

How could you frame your inputs and outcomes in an OKR system like Google’s?

Given your answers above, how would you fare in a Kimberly Clark or Netflix type PE system?

Would your bosses or investors pay you more to keep you based on your outcomes?