Neymar, the Brazilian born soccer star, is the most expensive player in soccer’s history with a salary reported at $38 Million Euros. In 2017, his pro team, Paris Saint-Germain, paid a $220 million transfer fee to obtain him. The problem is that he has under-performed since his arrival and sits the bench much of the time. Unlike LeBron James and his powerful effect on the Miami Heat’s ticket sales, Neymar is not a boost to Paris Saint-Germain’s box-office returns, to put it mildly.

Neymar wants to be traded and the team’s owners would like to make that happen. The problem is that no other team is willing to match the contract, let alone pony up for the transfer fee. Consequently, the team is stuck with a very costly star who adds nothing to the bottom line. Meanwhile, the team is losing games, fans, and money.

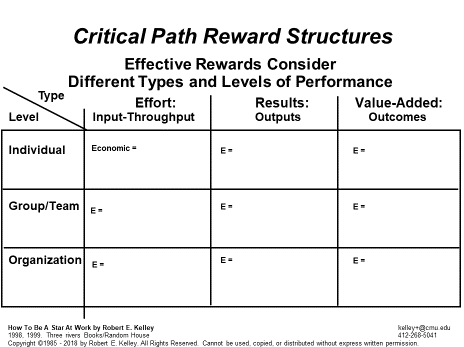

As we saw in the previous chapter, Paris Saint-Germain’s problem stems from not fully grasping how to align rewards to different types of performance (i.e. inputs, throughputs, outputs, or outcomes) and levels of performance (i.e. individual, team, or organizational).Once we successfully distinguish between types and levels of performance, then we need to think clearly about how to reward each cell in our matrix.

This is where many companies mess up because they put the wrong rewards in the wrong cells. Think about basic accounting, where you are required to match up short-term liabilities with short-term assets and then do the same with long-term liabilities and assets. Confusing the two can cause major headaches.

In a similar way, rewards for effort should not be confused with rewards for value-added outcomes. More importantly, you should not give rewards for organizational-level value-added outcomes to workers who are only giving you individual-effort inputs and throughputs. Doing so only affirms those workers’ behavior, sending the rather direct message that continuing to do exactly what they have been doing will not only be tolerated but rewarded—in other words, steering them directly away from the critical path.

To make this easier to understand, let’s first think about how different types of economic rewards should be allocated to each particular cell. (We’ll look at other types of rewards later.) Take a moment to fill in the framework below as to how your organization allocates different monetary rewards. Where do they put your salary, bonuses, stock options, etc.? Do they reward teams? If so, how?

Now, let’s look below at a more systematic way to pay people, one that supports the critical path and avoids motivating people away from it.

As we discussed earlier, salary should be base pay for effort inputs and throughputs. This will be applied at the individual, team, and organizational levels.

Bonuses should only be paid to those individuals and teams who actually produce critical-path result outputs or value-added outcomes. As we saw earlier with Google’s OKRs, giving someone a bonus for achieving their goal of going to a conference, i.e. fulfilling a throughput, makes no sense. This is the problem that many government agencies and school systems have encountered. They pay employees bonuses for going to conferences, taking classes, or getting additional certifications without any demonstration that those inputs yield current or future value. (As an aside, this also contributed to the rise of for-profit online universities, which provided these courses and certifications from the comfort of the employees’ homes and with very little quality control.)

Likewise, giving across-the-board bonuses to everyone also sends the wrong message to those who are only giving you inputs and throughputs. Instead, tie bonuses to results. Look again at the table above: bonuses only appear in the “Results” column.

Organizational result outputs, i.e., reaching important critical path goals such as making a significant profit off a new product launch or winning a major new customer, may call for profit sharing. The company may dig into its retained profits to share some of them with the entire workforce under the rationale that everyone did their part to make the achievement happen. This reward could be an end-of-year bonus or an extra day off with pay.

Rewards for value-added outcomes, as for result outputs, need to be contingent on actual achievement. Marty Cagan, the Silicon Valley product management guru, wrote about good product teams vs bad product teams: "Good teams celebrate when they achieve a significant impact to the business KPI’s. Bad teams celebrate when they finally release something." As such, organizations need to reward substantially the individuals and teams above their salaries because they are the folks who make the organization successful. Align and calibrate these rewards with the value produced.

Critical Path Action Items

Using the above framework, how does your organization allocate its economic rewards?

How does that allocation work against critical path outputs and outcomes?

How would you change that allocation to reinforce the critical path?