We can go a step further than we did in the previous lesson. It’s not only important for executives to know the company’s customers. It’s actually the job of everyone in the company to know the customers—and not just the current ones, but potential customers as well.

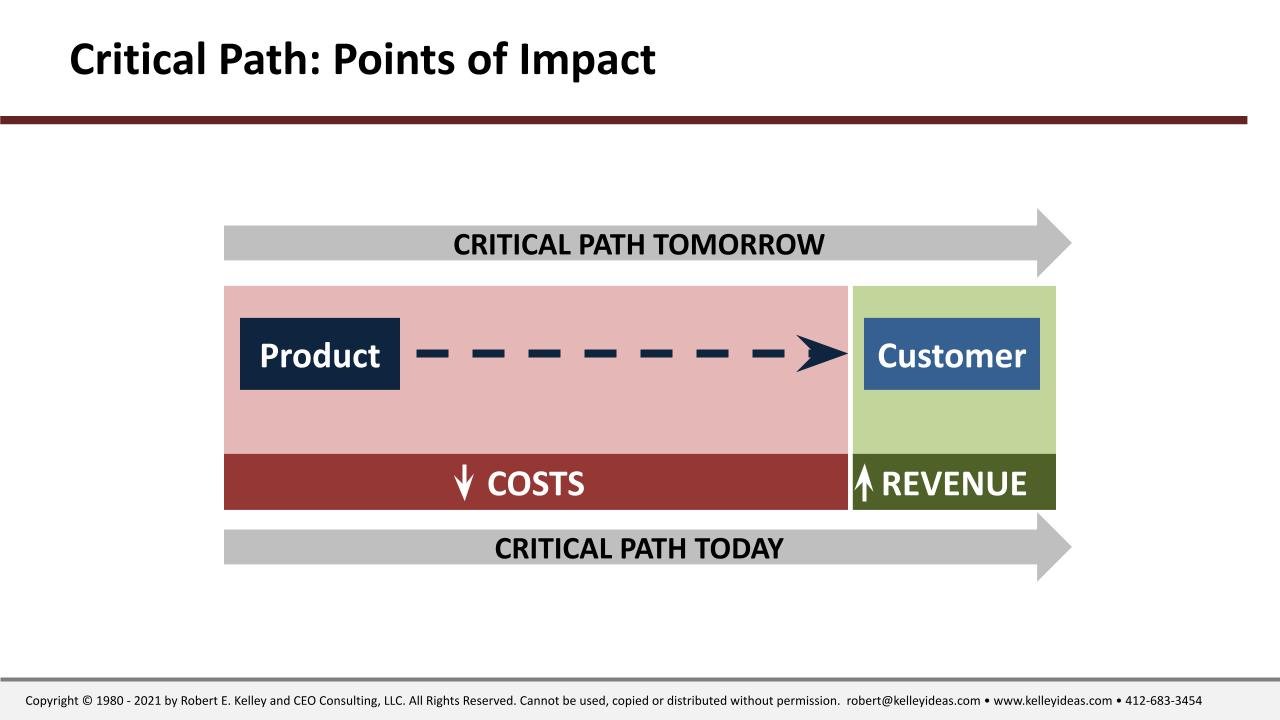

The better you know your customers, the better you can create and contribute to a critical path that creates a win-win for both them and you: a relationship where they feel they are getting products/services of real value to them, and where the company is getting highly satisfied, profitable, repeat customers in return.

Barbara, a CEO of a large tech company, ran into a triple whammy. First, customers complained that they were not getting a fast enough response to their questions and problems. Second, her staff blamed one another. Sales pointed the finger at the operations people, while operations blamed both the sales and customer support departments. Third, her top executives did not know the company’s customer base. They were siloed into their own functions and believed that only sales had to worry about customers.

Barbara took a page from Bob Galvin’s playbook. Bob Galvin was a former CEO of Motorola. During his historic tenure, the company’s revenues grew from $216.6 million to $6.7 billion and cash flow per share had grown from 89 cents to $6.10.

When Galvin ran into the same problem at Motorola as Barbara in her tech company, he did something that was then unthinkable. He drew up a list of Motorola’s top customers. He then divided the list, giving an equal number to each of his direct reports—about 10 apiece. He informed them that they were now responsible for their customers’ satisfaction, sales, and revenues. Moreover, he was going to give those customers the contact info of the top executive assigned to them and promise those customers that the top executive would respond to any queries within 2 hours, if not sooner.

His top executives did the expected—they complained vociferously.

“I’m in HR. What do I know about these customers?”

“Don’t you want me to do my job rather than sales’ job?”

“What if I’m in a meeting or have to meet a deadline? Do you want me to stop what I’m doing just to answer some customer’s call within 2 hours? Isn’t that too short of a fuse?”

“I’m trained as a lawyer, not in business. I’m better used in the courts than with customers.”

Galvin listened patiently and then explained that Motorola’s customers were the business and that every employee has customer responsibility. He was only asking them to do what he expected every employee to do—that is, to put the customer and the critical path first. How could he expect Motorola’s other employees to do that if the top executives didn’t do it? In fact, the top executives had to role-model it to send the message.

Bob Galvin’s audacious move produced a significant culture change at Motorola. Once the top executives had customer responsibility for satisfaction and profits, they started talking to those customers and, more importantly, listening to their concerns about dealing with Motorola. In particular, they heard about quality problems. This led Motorola to create and pioneer “Six Sigma,” a method to reduce product defects and quality variability. To achieve Six Sigma, Motorola had to show that 99.99967% of its processes and products were error free. Another way to look at it is that Motorola had 3.3 parts per million defects or less. This turnaround resulted in Motorola winning the first Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in 1988, which was given by the President of the United States.

Jack Welch of GE famously copied the Six Sigma page from Galvin’s playbook and made it his rallying cry at GE, where he claimed that it changed GE’s DNA. It is now commonplace in companies across the globe with Six Sigma Black Belts inside most organizations. But it all started with Bob Galvin forcing his top executives to pay close attention to their customers.

So, back to Barbara, our tech company CEO. After she assigned customer responsibility to her top executives, she faced the same reactions thrown at Bob Galvin. Like Galvin, she stuck to her plan, and however slowly and grudgingly, the executives got on board. Customer complaints are down, and satisfaction is up. As importantly, her team is now focused on customers and the critical path. In staff meetings, she has noticed a big change. Prior to the shift, her top executives really didn’t listen closely to each other’s reports about their areas. Now, everyone listens closely when the sales chief reports on customers, when the operation’s VP discusses customer complaints, and when the CFO discusses sales and profits by customer and customer segments. They are a team with a customer focus rather than a collection of solo players in separate functions.

Critical Path Action Items

Who is assigned to your company’s top customers?

Do “siloes” in your company interfere with serving your customers?

What could you do to know your customers better?