Part Three: How Companies Get off the Critical Path

To paraphrase Lewis Carroll in Alice in Wonderland, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.” When employees are not driven by the company’s critical path, they will often take other, unproductive paths. Sure, they will be busy, but they will not be productive.

Companies and employees get off the critical path in big ways and small ways. Surprisingly, top executives are sometimes the main culprits for getting the workforce off the critical path. For example, they will ask people to chase down some nonessential information. Simultaneously, workers will also go off on tangents, like surfing the web or getting bogged down in email, that distract them from the critical path.

A major cause can be referred to as “make-work.” These are all the tasks that add no value, like bureaucratic red-tape or internal politics, but use up people’s time and energy.

Make-work drives up costs and lowers productivity. It’s such a frequent cause of companies getting off the critical path, we’ll focus on make-work in a later lesson.

Taken together, all these wrong turns off the critical path send a signal that the critical path is not all that important. Your job is to eliminate all these side roads so that you and the company only give attention to the critical path.

Lesson 25: How Companies Get Off the Critical Path in Big Ways

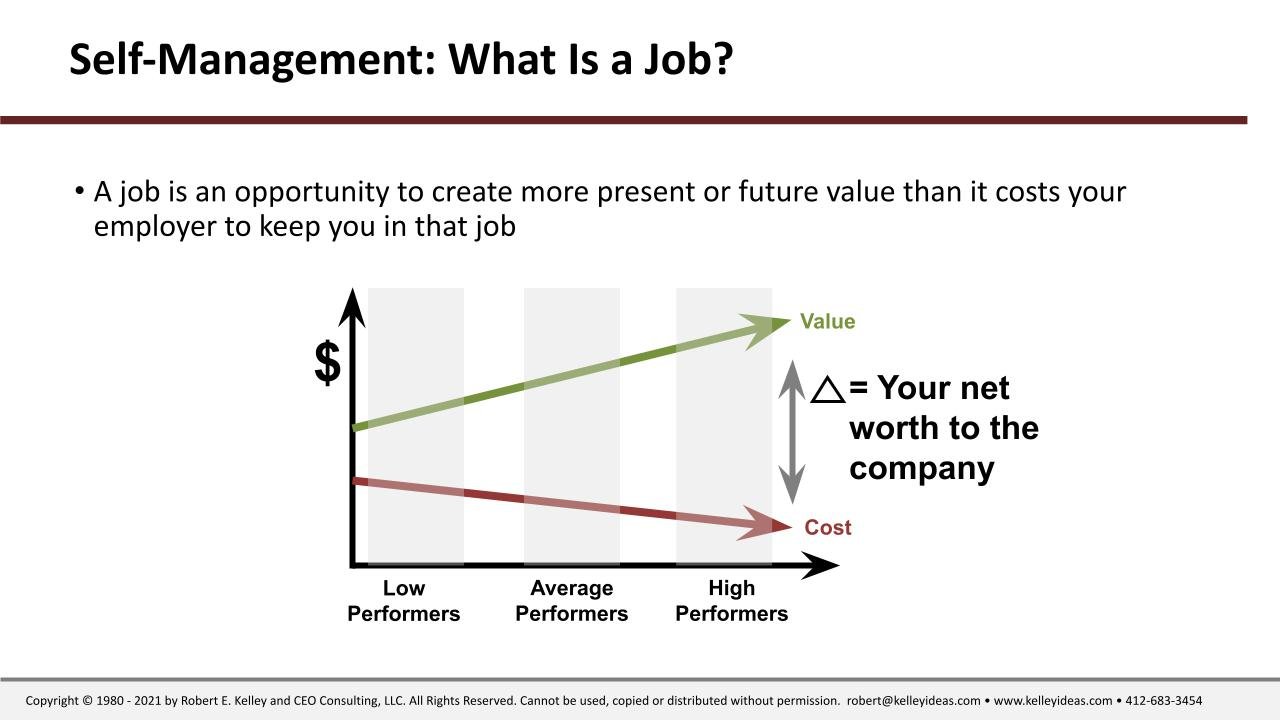

In many companies, the lowest performers are also the most costly to the company. This occurs for many reasons:

Low performers produce less and often create more errors, which leads to costly re-work.

Low performers can drag down the productivity of their colleagues by interfering with co-workers’ critical path contributions, e.g., interrupting them.

Low performers require more training and assistance from co-workers and management.

Low performers can have other issues, such as higher absenteeism and safety problems.

Low performers are more likely to get off the critical path or cause problems on the critical path.

Low performers use up more of their manager’s time and bandwidth, i.e. more of the manager’s salary is devoted to low performers and keeps those managers from doing work which contributes more to the critical path.

A large industrial company studied the top 100 employees and the bottom 100 employees from their 8 manufacturing locations. The salaries of both groups were nearly identical with the top performers averaging only 5% more pay. But the bottom 100 had much higher “other” costs, such as disciplinary issues, absenteeism, and on-the-job-injury claims. At the same time, the output of the top 100 was 5–7 times higher than the bottom 100.

Strikingly, this company had tolerated the bottom 100 for years. They had instituted Performance Improvement Plans (PIPs), but to minimal effect. Supervisors made excuses, such as workers were trying or had issues at home. The other workers just accepted that the bottom 100 were a fact of life. If management was OK with it, then they would have to be.

The company reluctantly realized that the bottom 100 were not going to improve and that they could (and should) fire them. They finally took that action both to improve overall productivity substantially and to reduce the higher cost of the bottom 100. The biggest effect, however — more than the cost savings of this move — was that the top 100 saw that management was finally focused on productivity and on those workers who really added value.

But, the bottom 100 are, metaphorically speaking, just the tip of the iceberg. They are an obvious problem, but not the only problem nor the biggest problem.

Consider what happened to JC Penney, the mid-level department store. Its revenue and stock price had been deteriorating when the Board of Directors hired Ron Johnson as the new CEO. Johnson had previously worked at both Target as a merchandising director and then Apple for 11 years where he led the Apple Stores to the highest sales per square foot in the industry. Penney’s Board, pushed by hedge fund manager William Ackman, hired Johnson hoping he could work his Apple magic on JC Penney.

Both Johnson and Ackman observed that Penney’s Plano, TX headquarters was bloated and mismanaged. Its 4,800 employees seemed overstaffed with assistants, merchandising personnel, and managers with few reports. Worse, according to Michael Kramer, JC Penney’s chief operating officer whom Johnson had brought along from Apple, those 4,800 HQ employees had watched 5 million YouTube videos during working hours in January 2012 alone. Ackman is quoted by the Wall Street Journal as saying that 20% of the company’s bandwidth went to Netflix. Combined with the YouTube videos, over 35% of the company’s entire HQ bandwidth was eaten up by social loafing.

5 million YouTube videos in just one month. Let’s break that down.

5 million videos divided by 4,800 employees = 1,041.67 videos per person

1,042 videos divided by 21 work days = 48 videos per day

48 videos divided by 8 hours = 6 videos per hour

6 videos divided by 60 minutes = 1 video every 10 minutes.

Of course, this isn’t even taking into account the time spent on Netflix, Hulu, or any other streaming service.

Let’s give these employees the benefit of the doubt and say that some were looking at fashion show videos to make merchandising decisions. Or, maybe others streamed music video playlists all day, instead of using Pandora, Spotify, or their own music collections, but did not actually watch the videos because they were busy working. And maybe some of those YouTube playlists never got turned off and played continuously for 24 hours/day (or about 360 videos for every 24-hour period with the average video length at 4 minutes), though the odds of a significant portion of the 4,800 employees doing so is very low. Or maybe the COO exaggerated, and it was only 2.5 million videos, which brings it down to a video every 20 minutes by every employee.

Even if we finesse them, the numbers are still staggering, and they still don’t account for the 20% of bandwidth eaten up by Netflix or the additional 15% taken by other video streaming usage. Clearly, a sizable number of HQ employees, who should have known better, got off the critical path. (Way off the critical path.) They thought their job was watching videos, not selling clothes to paying customers, and the company paid the price for it in dropping sales, profits, and share price. Does it surprise anyone that Johnson called in Bain, the management consulting firm, to conduct a productivity audit and ended up laying off 1,600 HQ employees—a full one-third of the Plano staff?

So, in JC Penney’s case, it wasn’t just the bottom 100 workers who were the problem. It was a large percentage of the 4,800 HQ employees who got off the critical path.

While it’s easy in a case like this to point the finger at the workers, wondering what they were thinking, the JC Penney example also raises question about upper management. What were they thinking, and how did they allow this to happen? Why did they need 4,800 people working at the headquarters instead of employing more of those people on the critical path’s front lines, servicing paying customers? Where was the chief information officer and why wasn’t she or he monitoring bandwidth usage? Why didn’t the CIO communicate the problem to other managers, or at least put in a filter that blocked out Netflix and YouTube? Where were the managers of all these video-watching employees? Were they busy watching videos themselves?

Now, video watching alone did not cause JC Penney revenue and profit problems. Top management made much bigger merchandising, store layout, and sale coupon mistakes that turned customers off. Rather, the fact that the video watching occurred was symptomatic of an entire company that had gotten off the critical path. From top management to bottom-level employees, the company was not focused on creating stores and merchandise where customers wanted to shop and buy. So, while we might chuckle over the 1,600 heavy video-watchers who lost their jobs, the blame for JC Penney’s demise rests first and foremost with top management.

Yes, upper management can also get people off the critical path by not keeping everyone focused on it. They can also do it when they don’t fully appreciate how their actions can distract employees. In another example, the CEO of a Fortune 200 company decided that the company was too fragmented into functions and that top managers were not on the same page. His solution was to institute “all hands” monthly review meetings for the top 10 executives with a separate day devoted each to strategy, business unit operations, marketing, finance, HR, or safety. They had to attend every corporate meeting, and these meetings typically took all day. They were also expected to bring any of their staff whom they deemed necessary.

Well, the top 10 executives wanted to make sure that their direct reports came to the meetings so that they were in the loop. This brought attendance up to around 60. Then, other managers who didn’t want to get left out wheedled their way into the meetings, bringing the total to 70.

Now, the CEO’s intentions were good: he was trying to solve an important problem. But the solution had serious unintended consequences. First, the meetings became important not because of the content discussed or the ideas they generated to solve the CEO’s communications problem. Rather, top employees felt a strong need to attend to be seen as major players in the organization by the CEO and his direct reports, as well as by the other attendees. Attending the meetings became a badge of honor, signaling that you were part of the power structure.

But many of the 70 people in attendance didn’t really need to be there because the subject matter of these meetings did not affect them directly. The all-day operations safety meetings, where new production line safety regulations were revealed, were a snooze-fest for the marketing, sales, and finance people. So although they were at these meetings, they stopped paying attention. Instead, they were looking through emails on their cell phones or trying to do other work on their laptops. It was estimated that less than 20% of the attendees were paying attention.

The fact that these meetings consisted of several hours of PowerPoint presentations didn’t help. Bulleted text slides after bulleted text slides added to the snooze-fest. Yet, because people were doing their show-and-tell to the top 70, they wanted their slide decks to look professional, with no errors or faulty data, since the CEO and top executives were quick to catch any mistakes and embarrass the presenter. This meant that the subordinates preparing the slides spent long hours getting the messaging and data just right. This, of course, took them away from even more important critical path work.

Still worse, the number of meetings expanded till these top 70 were at 9 all-day meetings each month. In other words, they were in corporate meetings about 45% of each month and year. That means this company spent about $8 million in salaries for these 70 people to attend these meetings—not including the salaries of the CEO and his top 10 executives. With them included, the cost ballooned to almost $26 million. This didn’t count the meetings they had in their own departments.

One result of all this was that in order to get their work done, these executives started working 12-hour days and coming in on weekends. In fact, it became so typical that people worked weekends that everyone, including lower-level staff, started coming in on weekends even if they didn’t have work to do. Face time became more important than actual work. They felt that they needed to be seen by the others and not viewed as slackers.

What started as a good idea became a major productivity millstone around the necks of these 70 executives and their subordinates, which turned into a stumbling block on the critical path. Did this company’s critical path improve by having their top 70 people in corporate meetings 45% of the time? What if they had instead devoted most of that time to the critical path? What about their subordinates who hopefully were focused on the critical path? Would they have been better served if their bosses weren’t out-of-pocket 45% of the year? Then, add in the effects from the morale issues caused by having to work 12-hour days and on weekends.

So, even CEOs and top executives can get their employees off the critical path—in big ways—as we saw with both JC Penney and the executive meetings.

Critical Path Action Items

What are the biggest ways that your company gets off the critical path?

How do top managers get people off the critical path?

What company practices get you off the critical path?