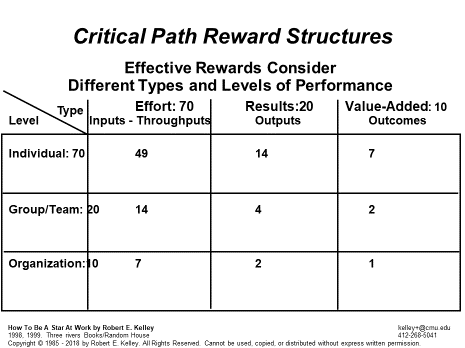

As a counterexample to the 90-10-0 weighting preferred by Grace, we can compare two other employees below. Rian is a novice TV writer who doesn’t know if his show will get picked up by a broadcast network, let alone be successful. Given that uncertainty, he prefers a 70-20-10 split for both type of performance (i.e., inputs, throughputs, outputs, or outcomes) and level of performance (i.e., individual, team, or organizational). Kate is also a TV writer, but has a string of past hits to her credit. She chooses a 20-30-50 distribution for type of performance and a 40-30-30 for the level of performance.

Rian’s risk/reward profile is more conservative, with 49% tied to individual effort and only 10% tied to any value-added outcomes. In contrast, Kate’s profile is more aggressive, with 50% tied toward achieving value-added rewards at all levels of the organization and only 8% focused on individual effort.

Which one do you think is going to work hardest on the critical path to produce value-added outcomes?

Organizations must determine the weighting that will align their employees to produce critical-path value-added outcomes. Then, they can focus on selecting people whose risk/reward profiles are compatible with that weighting. They should be open to people who are willing to be more aggressive since this signals a belief in their own capabilities to produce value and a belief in the organization’s potential to succeed.

The only people who should be able to negotiate a more conservative weighting, tilting toward individual effort, are those who have already proven that they create value-added outcomes. If those folks want to get less reward for their value, then that is one of the rewards to which star performers are entitled.

Once people negotiate their weighting, then they have to live with what they negotiated. Like Rian, if they opted for a conservative individual-effort weighting, then they can make no claim on the rewards that go to people who bet their rewards on value-added outcomes. If the company had a great year and is sharing the profits, they don’t get any more than they negotiated. Likewise, if the employee produces a value-added outcome that creates tremendous wealth for the company, they do not get to share in that benefit, unless the company chooses to be generous and do so. In Rian’s case, he would only expect get 7% of that individual value-added outcome.

In the alternative, employees like Kate with a higher risk/reward tolerance can get outsized returns if they and the company create high value-added outcomes to the bottom line, often many multiples of what their risk-averse colleagues earn. However, they make considerably less if they fail to make value-added output contributions or the company does not do well. In Kate’s case, she would take home 20% of her salary (or less) if she underperforms.

In other words, there are no “do-overs” till the next negotiation period. You live by what you negotiate until the next negotiation takes place.

The cast of the TV series Friends, were only paid $22,500 per episode in Year 1, even though the production company and Warner Brothers made huge profits off it. As the show became a hit, garnering 62 prime time Emmy nominations over its 10 year run, the cast re-negotiated their fee to capture more of the value added outcome they contributed -- $75,000 in Season 3, then $125,000 in Season 6, then $750,000 in Seasons 7 and 8, to finally $1 million each per episode for the last two years. Plus, they re-negotiated for syndication royalties, that is, a piece of the show's lucrative back-end profits. This means they get a cut of every time any episode is re-run. Netflix paid $100 million in 2019 to keep its most popular show on Netflix, and the cast members get a slice of that.

This no “do-over” goes for everyone in the organization. Unfortunately, numerous organizations have bailed out their CEOs when company performance did not exceed the hurdles necessary to trigger the bonuses and stock options. Shareholders rightfully bristled to see their money wasted on under-performing executives, as did the rank-and-file who saw co-workers laid off when the executives did not deliver their value-added outcomes.

Critical Path Action Items

Figure out how your organization currently weights rewards in the framework.

While you are at it, using the framework, figure out what your preferred risk/reward profile is. Then compare yours to the organizations. Are you matched well or mismatched?

How might you alter your risk/reward profile to capture more of your value added outcomes?