Most experts on reward systems will tell you that money isn’t everything. In fact, it isn’t even the first thing. In my work with companies and their employees, I’ve found that the top 3 motivators are:

Leading-Edge Work — that is challenging and meaningful.

Leading-Edge Colleagues — to work with and learn from.

Leading-Edge Management — such as the boss’s capabilities, the culture, and the total reward system.

Money itself isn’t even in the top three.

Star performers seek out work that pushes the envelope. They want to be part of the next new thing. They want to create new stuff that dazzles the market. They want work that lights their fire, not dampens their spirit. They want to make a difference. Most of all, they don’t want to do the same old-same old.

They also want to work with, learn from, and even teach the very best. For example, Patti McCord, Netflix’s former Chief Talent Officer, recounted a conversation she had with one of Netflix’s star engineers. She told him that she was laying off the three engineers he managed. Instead of being angry or demanding, he was happy because, as he said, he wasted too much time correcting their mistakes.

His reaction led McCord to a powerful insight: The best reward you can give a stellar employee is equally stellar co-workers to work alongside. “Excellent colleagues,” she wrote, “trump everything else.”

It’s a powerful reminder that we need to look beyond economic rewards if we truly want to motivate critical path value-added outcomes. We need to recognize that employees look for and want to receive social and psychological rewards. In fact, some employees are willing to trade money for these rewards. It is not unusual for someone to accept a job that pays less but gives them the opportunity to work on innovative projects or with a brilliant scientist. In one company, the top performers were willing to forego a raise if they could have lunch once a month with a different top executive. They wanted to get to know their top bosses so that they could learn how to contribute better to the organization. They also thought that face time with the top brass would help them decide if they wanted to move onto the management track.

By introducing these other types of rewards, you can expand the possibilities of how to reward any individual or team. You can mix and match economic, social, and psychological rewards so that you customize a reward program that fits the employee. This is important because no two individuals are alike. Some may prioritize the work, colleagues, and a mentoring boss in that order, while others want recognition, money, and more influence.

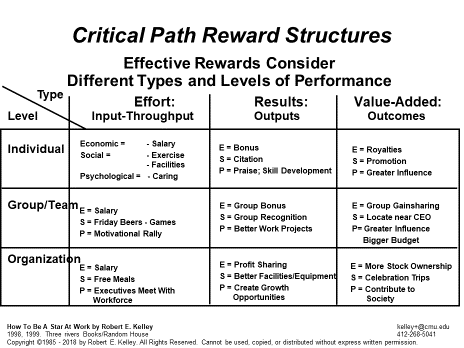

In light of that fact, below is an expanded reward framework that includes more than just economic rewards.

As with economic rewards, you must align the right rewards with the right cells in the framework. Just as you shouldn’t give royalties or stock for individual effort, you should not give away job promotions and celebration trips for anything but value-added outcomes. Promoting people based on seniority is generally not a good idea since it rewards longevity, not critical path performance. Similarly, celebration trips are not entitlements for every employee. Limit them to people who produce results and value-added outcomes.

The completed framework below gives examples of various social and psychological rewards tied to each cell. We differentiate between social and psychological rewards this way: social rewards recognize an employee publicly, or provide opportunities to connect more deeply with the company and co-workers; psychological rewards emphasize growth opportunities, personal development, and future prospects, sending the employee the message that he or she matters and that the company cares about her or his individual needs.

The framework below includes several examples of each type of reward. You might have others that you use. The important part is to match them properly to encourage critical path outcomes.

The important point is to ask workers what will work for them rather than assume that what works for you will work for them. Show people this framework and ask them what rewards they value and how they weight or prioritize them. Maybe they have an additional reward they want to include, such as more vacation time or more flexible working hours.

If you think that social and psychological rewards are not important, then let’s return to Paolo Pellegrini and Paulson & Co. Earlier, I mentioned that his decision to leave was partly due to compensation. Again, money often isn’t everything. Pellegrini also felt slighted by John Paulson who took most of the credit for Pellegrini’s success. As Greg Zuckerman, a Wall Street Journal reporter who covered the story, recounted in his book The Greatest Trade Ever:

“In January 2008, Paulson and Pellegrini visited Harvard University, their alma mater. Pellegrini was excited about the trip and looked forward to explaining to the students how the firm had anticipated the credit crisis. But when they got there and the class settled into their seats, Paulson approached the dais and addressed the group by himself, while Pellegrini watched from the back of the room. Later, Pellegrini helped his boss answer some questions from students, but it stung Pellegrini that he wasn’t invited to address the class. Paulson’s shadow never seemed so huge. ‘It was humiliating to me,’ Pellegrini recalls.

“Hell hath no fury like a hedge-fund manager scorned.”

Critical Path Action Items

Which economic, social, and psychological rewards have meaning to you?

How would you weight them and mix-n-match them?

Which rewards do you want for value added outcomes?

As an owner or manager, how have you aligned these different types of rewards to support the critical path?

How can you customize and personalize the rewards for value added outcomes?