LeBron James is arguably the most famous and popular basketball player in America, perhaps the world. When he first left the Cleveland Cavaliers and headed to the Miami Heat, season tickets for Miami sold out quickly for the next two years. The Miami front office was able to eliminate its Sales Department after he signed with the team because his signing made their job—reaching out to the public, drumming up ticket sales—completely unnecessary. LeBron not only increased revenues (sold out season tickets), he also reduced costs (the Sales Department). Were he not constrained by the NBA players union’s collective bargaining agreement, as well as the NBA’s salary cap, he could have bargained in his salary negotiations to receive the entire budget of the Sales Department because he effectively did all its work.

The team as a business, however, did benefit twice on the cost side from LeBron. First, the elimination of the Sales Department lowered the company’s cost which did not have to be shared with LeBron. Second, the salary cap imposed on star players like LeBron lowered their labor costs for top talent compared to what they would have had to pay him in a more competitive labor market, such as Major League Baseball, or a truly competitive labor market, such as Hollywood or CEO searches.

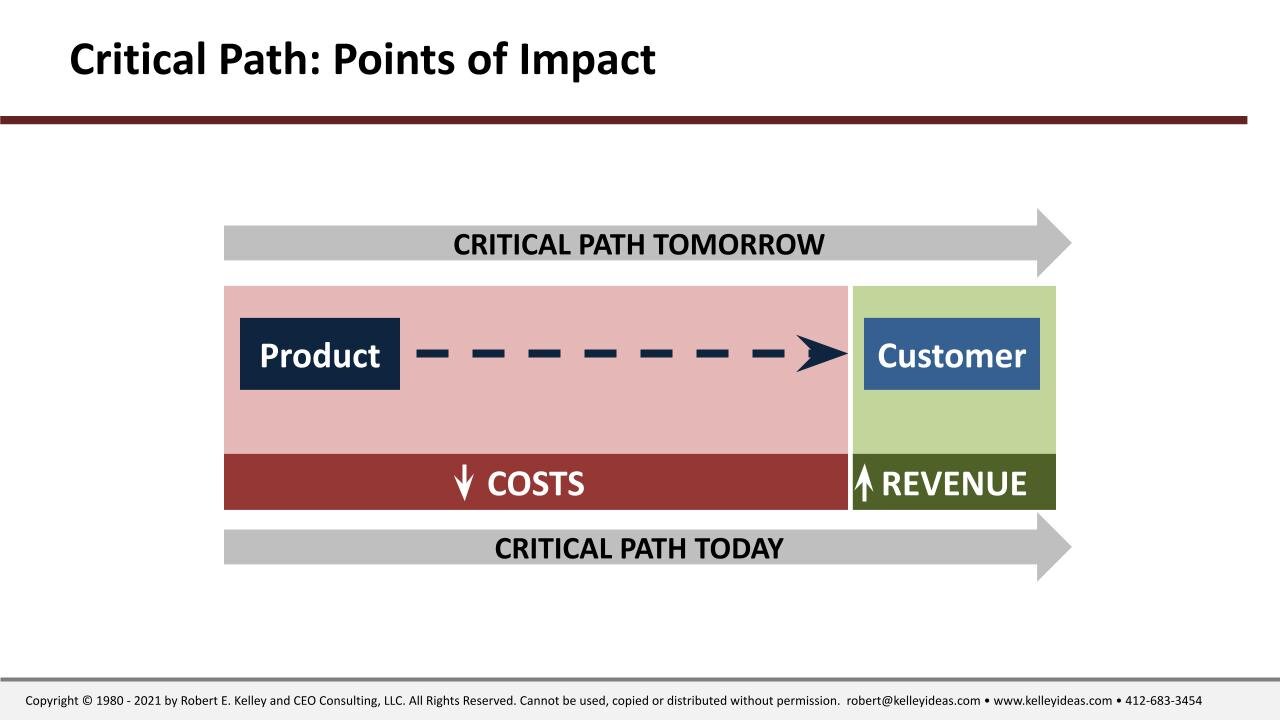

LeBron James exemplifies the fact that to create value and make a profit, companies work both sides of the equation: decreasing costs and increasing revenues. As an employee, you add value either by reducing costs on the critical path or by generating revenues on that path.

In the case of decreasing costs, the company continually looks for increased efficiencies to drive down costs (such as eliminating the entire Sales Department). As discussed earlier, unless your unique talents produce unique value for customers and profit for your company, you risk being seen as a cost, not as an investment. If the company can hire someone cheaper to do your job, you are history. If it can find a computer program to do your job, you are history. If it can send your job overseas where a highly educated replacement will work for 1/10th your salary, then you are history. If it can be more profitable by eliminating your position altogether and not filling it with any substitute, then you are definitely history.

To protect your downside, your goal is to not be history. On the upside, your goal is to make history. You do this by having assets that contribute real value to a company’s critical path (that is, the shortest distance between what your organization does and your profitable customers).

I’ll repeat: You add value either by reducing costs on that path or by generating revenues on that path. At the end of the day, the company must have enough revenues to cover all its costs and enough profit left over to make all their business operations worthwhile. If it cannot do this, then why bother? Why not just put the money it takes to start and run the operation into a bank and let it earn interest?

If you understand these simple principles, then you are on your way to adding value. In a later chapter, we will meet Corinne, a 26-year-old newly minted MBA whose starting job offer of $180,000 would seem to be a bit on the high side for such an untested employee. But as we’ll discover, such a high salary gives us a sense of how much a company expects that employee to earn for the firm. Hint: it’s a lot more than $180,000.

As an employee, you must add so much more value than your actual cost that it is efficient for the company to keep you around. At a minimum, you need to be a better value than either elimination of your position or your next closest substitute. Optimally, you add so much value that your organization is making so much money off of you that they heap money and rewards on you to entice you to stay. In other words, you add so much value that you are no longer viewed as a cost and the company instead starts investing in you like the good investment that you are.

Morten Hansen, a University of California Berkeley management professor, recounts a conversation with Hartmut Goeritz, a manager at the international shipping company Maersk. Goeritz’s responsibility was moving containers on and off ships at Maersk’s terminal in Tangiers, Morocco.

One day, as Mr. Goeritz walked among the trucks in the shipping yard, he noticed that some of the trucks were empty as they moved across the yard. “They picked up the container at the side of a ship,” he recounted of the dock workers, “then drove to the back of the giant yard to set it down, then drove back to the ship empty-handed to pick up the next one.” The drivers had done it this way for years.

What Mr. Goeritz saw was lots of lost time and wasted fuel. What if trucks didn’t go back empty? What if after dropping off their containers in the yard, they then carried back other containers destined for nearby ships that were loading? He met with the drivers to discuss the idea. He encouraged the truckers heading back to the ships to talk to their counterparts in the yard if they could pick up any waiting containers. Soon, loading crew and unloading crews began using walkie-talkies to coordinate this work to find more containers ready to ship out. The motto became “never drive empty.” Goeritz’s simple redesign nearly doubled efficiency, driving down costs at the terminal.

So, like Hartmut Goeritz, ask yourself, how do you help the company reduce costs or make money?

On the cost side, keep in mind: it is counter-productive to do exceptionally well a task or job that should never have been done in the first place.

With that mindset, could you:

eliminate some tasks or jobs you are currently doing that are unnecessary?

automate your necessary tasks so they are done faster, better, or more cheaply?

do your job more efficiently, cheaply, or in less time?

use technology to make your and other people’s jobs more efficient?

cut out some steps in how you do your job without having a negative effect on your output?

re-design your entire work flow (and, if possible the whole department’s work flow) to make it more efficient?

reduce the amount of quality control problems you see that then require re-work?

spend less downtime either goofing off or redoing work?

interface more smoothly with other departments?

help your colleagues get their jobs done more quickly and with better quality?

get better prices from suppliers to you, your department, or the entire company?

work with suppliers to obtain better quality materials at the same or lower costs?

use less quality and/or less expensive materials without any effect on your products’ or services’ overall quality?

The goal of these cost-cutting questions is not to cut costs just for the sake of reducing expenditures. The goal is to reduce costs by being more efficient and productive. To the extent that you help your company do so, you are making the critical path to your customer shorter, faster, smarter, better, and more effective.

But adding value on the cost side will only take a company so far. Sure, the company can make its financial picture look good temporarily by laying off employees, postponing machine maintenance, or delaying paying its suppliers. But at some point, it can no longer squeeze meaningful gains out of the cost side. Once a company has cut away all the fat, cutting into the company’s muscle or bone will cause nothing but harm, damaging its future prospects.

The goal, then, is to improve the company’s and your performance generated by its investments. Costs may be worth keeping when they lead to higher asset productivity or give you and the company greater leverage on the revenue side.

Critical Path Action Items

What costs can be taken out of your company’s critical path?

How would it improve the efficiency of the critical path?

How much money would it save?

Would that cost reduction have a negative effect on or improve your customer relationships?